Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900)

Identifier: va_1603a

Commentary on Duke of Sessa’s Petition on behalf of Giovanni Tallino, Rome (1603)

Jane C. Ginsburg

Please cite as:

Ginsburg, J.C. (2022) ‘Commentary on Duke of Sessa’s Petition on behalf of Giovanni Tallino, Rome (1603)', in Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), eds L. Bently & M. Kretschmer, www.copyrighthistory.org

1. The Privilege

2. Transfers of rights in privileges

3. Persons mentioned in the Petition or Privileges

This petition is an example of a request made by an important patron, often a high-standing cleric, but in this case a Spanish nobleman, Antonio Fernández de Córdoba y Cardona, Duke of Sessa, on behalf of Roman publisher Giovanni Tallino, seeking revocation of prior privilege granted to Miquel Llot for printing the Summa of St. Raymond of Peñafort, and transfer of the privilege to Tallino. (For petitions by or invoking ecclesiastical patrons see, e.g., Arm XL v 49 F 204 (n 235) (Dec. 5, 1534) (petition of the humanist and Bishop Claudio Tolomei on behalf of his relative Mariano Lenzi); Sec. Brev. Reg. 199 F 172 (Jan. 26, 1593) (Cardinal Cinzio Aldobrandini on behalf of painter Cesare Ripa); Sec. Brev. Reg. 239 F 382 (May 26, 1596) (petition of Fra Giovannni Baptista Cavoto invoking Cardinal Aldobrandini); Sec. Brev. Reg. 303 F 390 (Dec. 16, 1600) (Cardinal Aldobrandini on behalf of printer Antonio Franzino).)

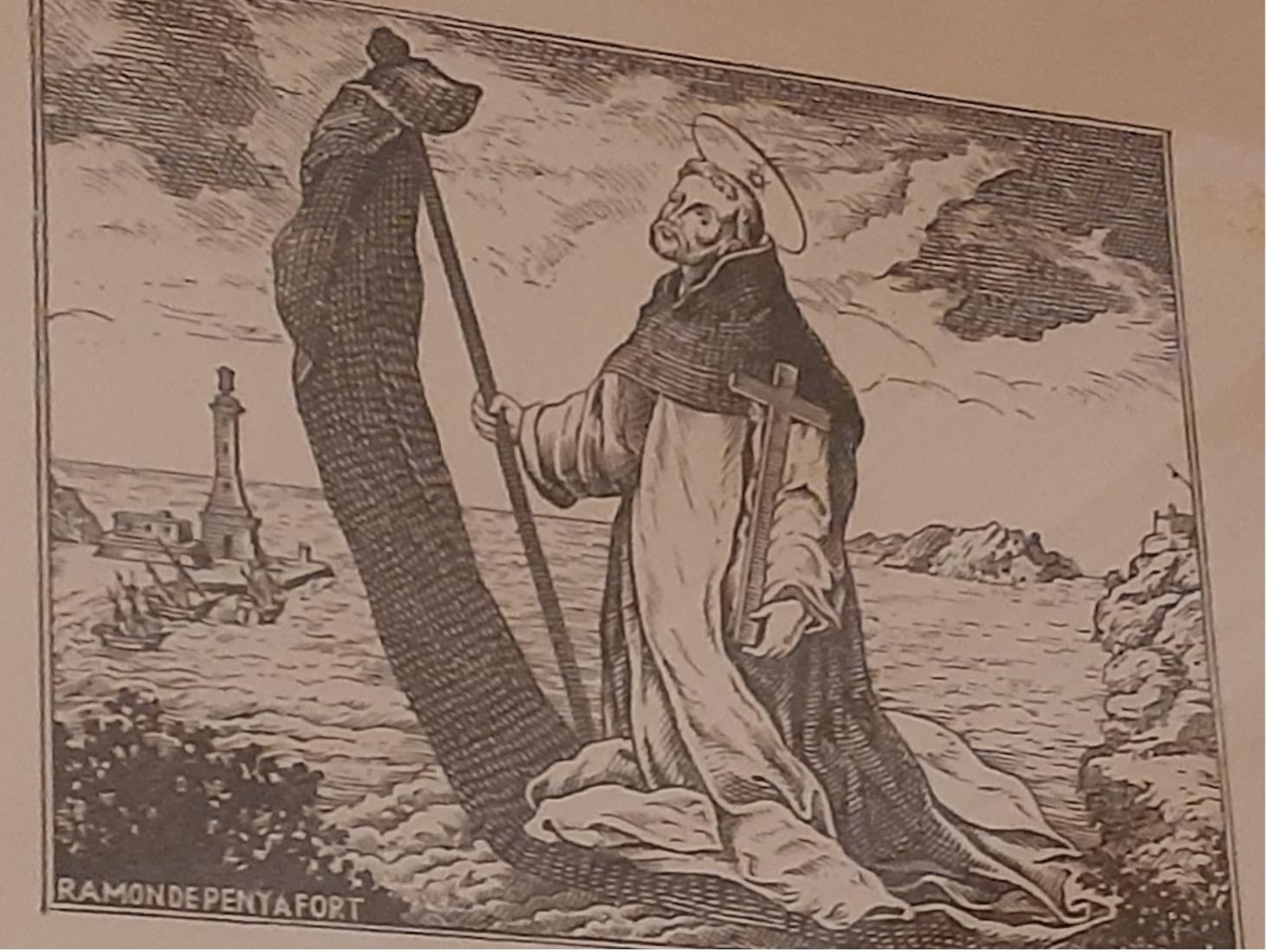

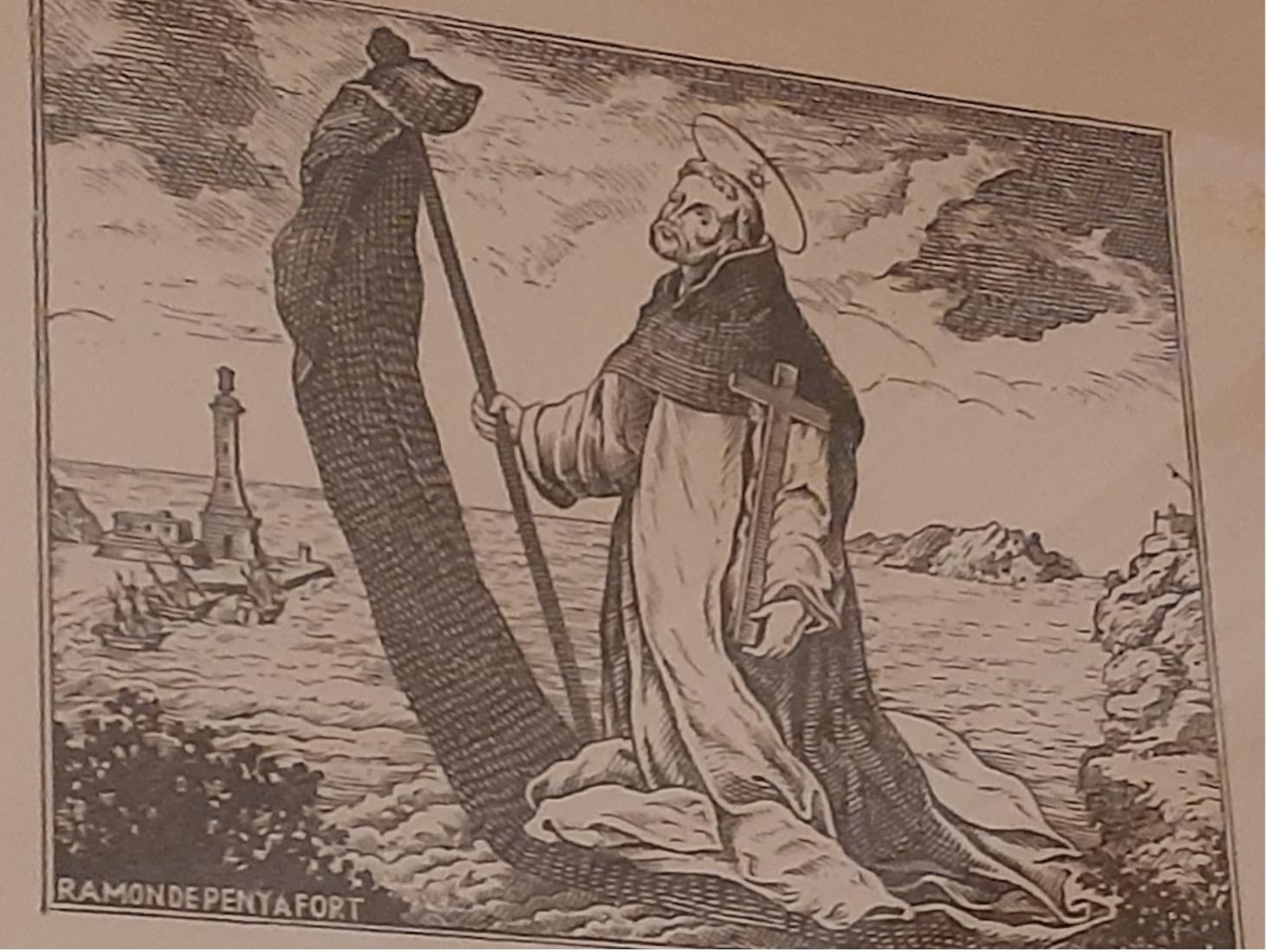

Llot, a Catalan Dominican, had lobbied for the canonization in 1600 of Raymond of Peñafort, a renowned Catalan canon lawyer (who became the patron saint of lawyers, and whose effigies today adorn the palace of the Barcelona Bar Association). In conjunction with the canonization, Llot obtained a privilege over a summa he compiled of Peñafort’s works. A 1600 edition of the Summa, combining Peñafort’s Summa de poenitentiis with his later Summa de matrimonio, together with commentaries by Dominican theologian Johann of Freiburg (? - 1314), was printed and initially distributed in Rome by Domenico Gigliotti (1575~1603). Llot’s 1600 privilege would have been in force until 1610. The 1600 edition has been digitized and is available via this link. It appears, however, that Llot abandoned the project and ceased paying his printer, who then embargoed the remaining copies. Tallino agreed to pay the debts to release the books, but on condition that Llot’s privilege be transferred to him. The 1603 edition confirms the transaction, for it declares that the book was printed “at the expense of Giovanni Tallini” (“sumptibus Ioannis Tallini”).

1. The Privilege

The handwritten Privilege includes text recycled from a prior privilege to different printers for an unrelated book. While privileges tend to be formulaic, with the same expressions recurring across a great number of grants, not many examples exist of cutting the pages of privileges printed in prior books, and pasting them into the new grant. (For one such example, see https://www.copyrighthistory.org/cam/tools/request/showRecord.php?id=record_i_1534, Melchiore Sessa’s privilege for works of Lodovico Martelli, recycled from a prior privilege to Antonio Blado for works of Machiavelli.)

Apart from the revocation and transfer, the terms of the privilege are fairly standard: a ten-year duration from the first printing (in this case the privilege would have run from 1600, rather than the privilege’s reissuance in1603); a prohibition not only on reprinting the work in its original format, but also in different formats and in versions with additions or deletions of text. Remedies included confiscation of books and typefonts, and a fine of 500 ducats, divided three ways, among the Papal treasury; the beneficiary of the privilege (Tallini) and anyone holding a cause of action from him; and the accuser and executing judge (perhaps to ensure zealous enforcement of the privilege).

2. Transfers of rights in privileges

While Tallini acquired rights by compulsory transfer, the privileges generally specified the requirements for the validity of voluntary transfers. Regarding licenses or transfers of rights covered by the privileges, the Papal grants generally barred third parties from printing or selling the work without the privilege holder’s authorization, and frequently required that the authorization be “express” and/or in writing. See, e.g., Sec. Brev. Reg. 69 F 270 (Jul. 15, 1581) (to Marcello Francolini for his book on canonical hours); Sec. Brev. Reg. 120 F 261 (Jun. 3, 1586) (to Girolamo Catena for his Life of Pius V); Sec. Brev. Reg. 304 F 272 (Jan. 3, 1601) (to Antonio Valli da Todi for his book on bird songs).

Once granted, privileges acquired the attributes of property, because they could be inherited and transferred: privileges routinely referred to the grantee’s heirs, rightholders, and successors in title. Some of the privileges granted to authors specify that the rights may pass to the printer chosen by the author, or that others may not print without the permission of the author and/or the printer chosen by the author. See, e.g., ARM XLI vol. 21 F 458 (Jul. 19, 1541) (law book on pensions by Girolamo Giganti, privilege granted to author refers to the printer Giganti will have selected: “impressori per te eligendo”); Sec. Brev. Reg. 278 F 103 (Jan. 8, 1599) (to Giovanni Cecca for medical book; “quos ipse ad huiusmodi operis impressionem faciendam elegerit”; the petition requests “che nessuno possi stampare ni far stampare una opera mia di certi consiglij et de pulsibus la quale sono per dare in stampa eccetto che il stampatore quale sera da me a questa opera eletto” – “so that no one may print nor have printed a work of mine on certain medical counsels, except for the printer that I shall have chosen for this work”); Sec. Brev. Reg. 285 F. 86rv, 87 rv (petition) (Jul. 4, 1599) (author, Spanish theologian Pietro Hieronimo Sanchez de Liçaraço, names licensee, Francesco de Heredia, who should have book printed in author’s name).

While authors, rather than printers/publishers/booksellers, frequently were the initial beneficiaries of Papal privileges, and subsequently transferred or licensed rights to the latter, printers (etc.) also applied for and received privileges, often for the works of (long) deceased authors. In the course of the 16th century, when the authors were living, petitions for privileges sought by printers or third parties other than the author or his heirs, or the texts of the privileges themselves, increasingly adverted to authors’ or heirs’ authorization to the printer to obtain the privilege. Thus, for example, in 1593 the painter Cesare Ripa sought a privilege for an iconology, but before the privilege issued it appears that Ripa authorized the heirs of the printer Giovanni Gioliti to publish the work. The ensuing breve grants the privilege to the printer’s heirs “as far as they have the cause of action from the same Cesare.” See Sec. Brev. Reg. 199 F 172r (Jan. 26, 1593). Similarly, best-selling law book author Prospero Farinacci complied with his printer’s behest to accompany the printer’s petition with a letter endorsing the latter’s request for a privilege on a new edition of Farinacci’s treatise on criminal practice. See Sec. Brev. Reg. 301 F 19, 20r (petition) (Oct. 31, 1600). To the same effect, see Sec. Brev. Reg. 347 F 12rv (Jul. 1, 1604))

3. Persons mentioned in the Petition or Privileges

Pietro Aldobrandini (1571 – 1621). Italian Cardinal and patron of the arts, made cardinal in 1593 by his uncle, Pope Clement VIII.

Marcello Vestrio Barbiani (? – 1606). Cardinal-Secretary of Brevi (papal letters). The son of a famous lawyer, Barbiani joined the Papal court after his wife, a Roman noblewoman, passed away. In 1596, he was granted a canonicate in the Vatican Basilica. Barbiani served in various capacities under Gregory XIV, Clement VIII, and Paul V, before passing at a very old age shortly before July 9th, 1606. See Giammaria Mazzuchelli, Gli scrittori d’Italia. Vol. 2,1 at 178 (1758).

Antonio Fernández de Córdoba y Cardona, Duke of Sessa (1590–1606). Son of Fernando Folch de Cardona, Duke of Soma, and Beatriz Fernández de Córdoba, Duchess of Sessa. While in the royal court in Madrid, he served as a menino (companion) of Infanta (Princess) Juana de Portugal, the sister of Felipe II. In 1590/1, Felipe II appointed Antonio ambassador to the Holy See, and Antonio received the Duchy of Sessa in the same year. In April 1601, Antonio (by now Duke of Sessa) saw the canonization of St. Raymond in Rome. Antonio ceased serving as ambassador to the Holy See in 1603, and he died in 1606. See generally Miguel Ángel Ochoa Brun, Antonio Fernández de Córdoba y Folch de Cardona Anglesola y Requesens, Db~e (last visited Oct. 28, 2021).

Johann of Freiburg, German theologian, d. 1314. Inspired by St. Raymond’s Summa, Johann synthesized St. Raymond’s work with the writings of Thomas Aquinas into the encyclopedic Summa confessorum. See also WorldCat / Google Books, for a 1518 printed edition.

Miquel Llot de Ribera (1555 – 1607). Spanish Dominican theologian and member of the Congregation of the Index. He was the original recipient of a papal privilege to print the Summa of Sti. Raymundi de Peniafort…. This original privilege is preserved in print form in a 1600 edition of the Summa, which was printed in Rome by Domenico Gigliotti (1575~1603). This 1600 edition has been digitized and is available via this link.

St. Raymond de Peñafort (1175 – 1275). Dominican friar from Catalonia and the patron saint of lawyers. In addition to writing a manual for confessors, Summa de casibus poenitentiae, St. Raymond compiled a definitive collection of canon law, Decretales Gregorii IX (also referred to as Liber Extra) at the bequest of Gregory IX, disseminated in 1234. For more on the significance of this work, see The History of Medieval Canon Law in the Classical Period, 1140-1234, Wilfried Hartmann and Kenneth Pennington, eds. (Washington: Catholic University of America Press, 2008.

It is said that while serving as the confessor for King James I of Aragon on Mallorca, St. Raymond sought to leave the king’s service in light of James’ immoral behavior. Though King James forbade St. Raymond from leaving Mallorca, the friar tied his cloak to the ends of his walking stick, and miraculously sailed on his makeshift raft and mast back to Barcelona. Moved by this miracle, King James repented. See Dominican Saints 101: St. Raymond of Penafort, Dominican Friars Province of St. Joseph (Jan. 7, 2012). The image below depicts St. Raymond’s journey across the Mediterranean.

Image in the collection of the Barcelona Bar Association

Giovanni Tallino [or Tallini], a bookseller active in Rome between 1599 and 1603. His name on publications was “Joannes Tallinus.” See Istituto centrale per il catalogo unico delle biblioteche italiane e per le informazioni bibliografiche, Full Record of Giovanni Tallino, EDIT 16 (last visited Oct. 28, 2021).